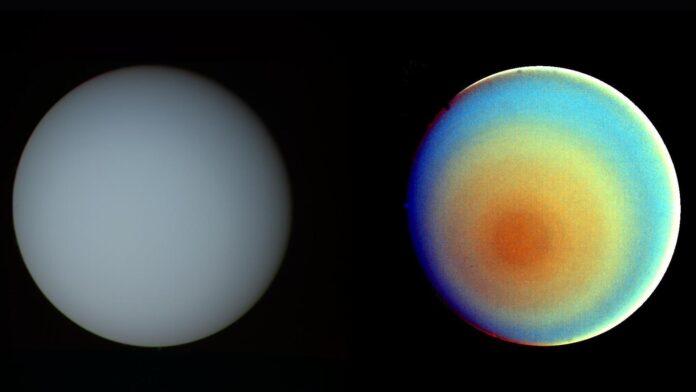

For decades, scientists puzzled over an unusually intense radiation belt detected around Uranus during the Voyager 2 flyby in 1986. New research suggests a temporary surge in solar activity may have supercharged the planet’s radiation field just as the probe passed by. This discovery isn’t just about Uranus; it sheds light on how planetary radiation belts form and behave – a critical understanding for space exploration.

The Voyager Anomaly

Voyager 2’s data revealed an electron radiation belt around Uranus far stronger than predicted. While the ion radiation was weaker than expected, the electron belt bordered on maximum intensity. This discrepancy baffled researchers, as standard models couldn’t explain such a powerful surge. The question became: was this a normal state for Uranus, or did something extraordinary happen during that specific window?

Earth’s Mirror: Space Weather Events

The breakthrough came from comparing the Voyager 2 data to recent observations of Earth’s magnetosphere. In 2019, Earth experienced a “co-rotating interaction region” – a collision between fast and slow solar winds. This event caused a massive acceleration of electrons in Earth’s radiation belt. Researchers realized that a similar event could have struck Uranus in 1986, temporarily amplifying its radiation field.

“If a similar mechanism interacted with the Uranian system, it would explain why Voyager 2 saw all this unexpected additional energy.” – Sarah Vines, space physicist at SwRI

Why This Matters

Understanding radiation belts is crucial for spacecraft longevity. Intense radiation can fry electronics, making long-term missions risky. Uranus, with its extreme axial tilt causing bizarre seasons, is a particularly harsh environment. If temporary space weather events can dramatically boost radiation levels, then future missions to Uranus (and similar planets like Neptune) need to account for these unpredictable surges.

The Case for a Uranus Orbiter

The current findings underscore the need for a dedicated Uranus mission. An orbiting probe could map the planet’s magnetosphere, monitor radiation levels over time, and confirm whether these surges are common or rare. The physics of Uranus’ magnetosphere remains largely unknown, and a mission would fill critical gaps in our understanding of ice giant planetary systems.

This discovery isn’t just about solving a decades-old mystery; it’s a reminder that even in the well-studied realm of space physics, surprises await. The Uranian system is far from passive, and its interactions with the Sun are dynamic and unpredictable.