For decades, the iconic Triceratops has been pictured as a powerful herbivore, its horns and frill the focus of paleontological study. However, recent research has revealed that the dinosaur’s oversized nasal cavity wasn’t just for scent—it played a critical role in regulating body temperature and breathing. A team led by Dr. Seishiro Tada at the University of Tokyo Museum has mapped out the soft-tissue anatomy of these horned dinosaurs, challenging previous assumptions about their cranial structures.

The Puzzle of the Triceratops Nose

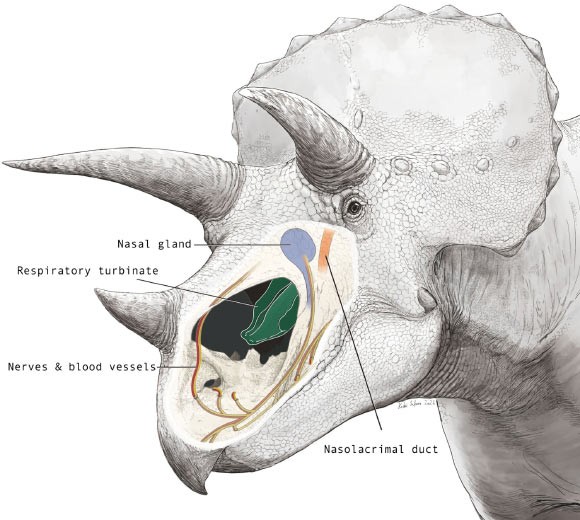

The nasal region of Triceratops was unusually large, and scientists struggled to understand how its internal organs could fit within it. Dr. Tada’s team employed CT scans and comparative anatomy with modern reptiles to reconstruct the soft tissues inside the skull. The results reveal that Triceratops had a unique “wiring” system for its nerves and blood vessels, differing from most reptiles where these structures reach the nostrils from the jaw. In Triceratops, the skull’s shape blocked this route, forcing the nerves and vessels to take a nasal branch instead. This suggests that the nasal structure evolved specifically to accommodate the dinosaur’s massive nose.

Respiratory Turbinates: A Key Discovery

The study also identified evidence of respiratory turbinates in Triceratops. These thin, curled nasal surfaces increase the contact between air and blood, helping to regulate temperature through heat exchange. While rare in other dinosaurs, these structures are common in modern birds and mammals. The presence of a ridge in the Triceratops nose—similar to where turbinates attach in birds—strongly suggests that the dinosaur used this feature to manage its body temperature, which would have been especially important given the size and heat-generating potential of its skull.

Why This Matters

This research fills a critical gap in our understanding of dinosaur physiology. Horned dinosaurs, including Triceratops, were among the most successful Late Cretaceous species, yet their nasal anatomy has been largely overlooked. The discovery of respiratory turbinates suggests that Triceratops wasn’t fully warm-blooded but likely used its nasal structures to maintain stable temperature and moisture levels. The findings also underscore how little we still know about the soft tissues of extinct animals, which often decay before fossilization.

“Horned dinosaurs were the last group to have soft tissues from their heads subject to our kind of investigation, so our research has filled the final piece of that dinosaur-shaped puzzle,” Dr. Tada stated.

Future studies will focus on the function of other cranial structures, such as the frill, to further refine our understanding of these magnificent creatures. This research marks a significant step forward in paleontology, demonstrating that even well-studied fossils can still hold surprising secrets.