A groundbreaking new brain-machine interface (BMI) uses light to communicate directly with the brain, bypassing traditional sensory pathways. Recent experiments with mice demonstrate a minimally invasive wireless device capable of delivering artificial inputs to genetically modified neurons, effectively “speaking” to the brain through patterns of light. This technology could revolutionize neuroscience research and hold promise for future prosthetic advancements.

How the Device Works

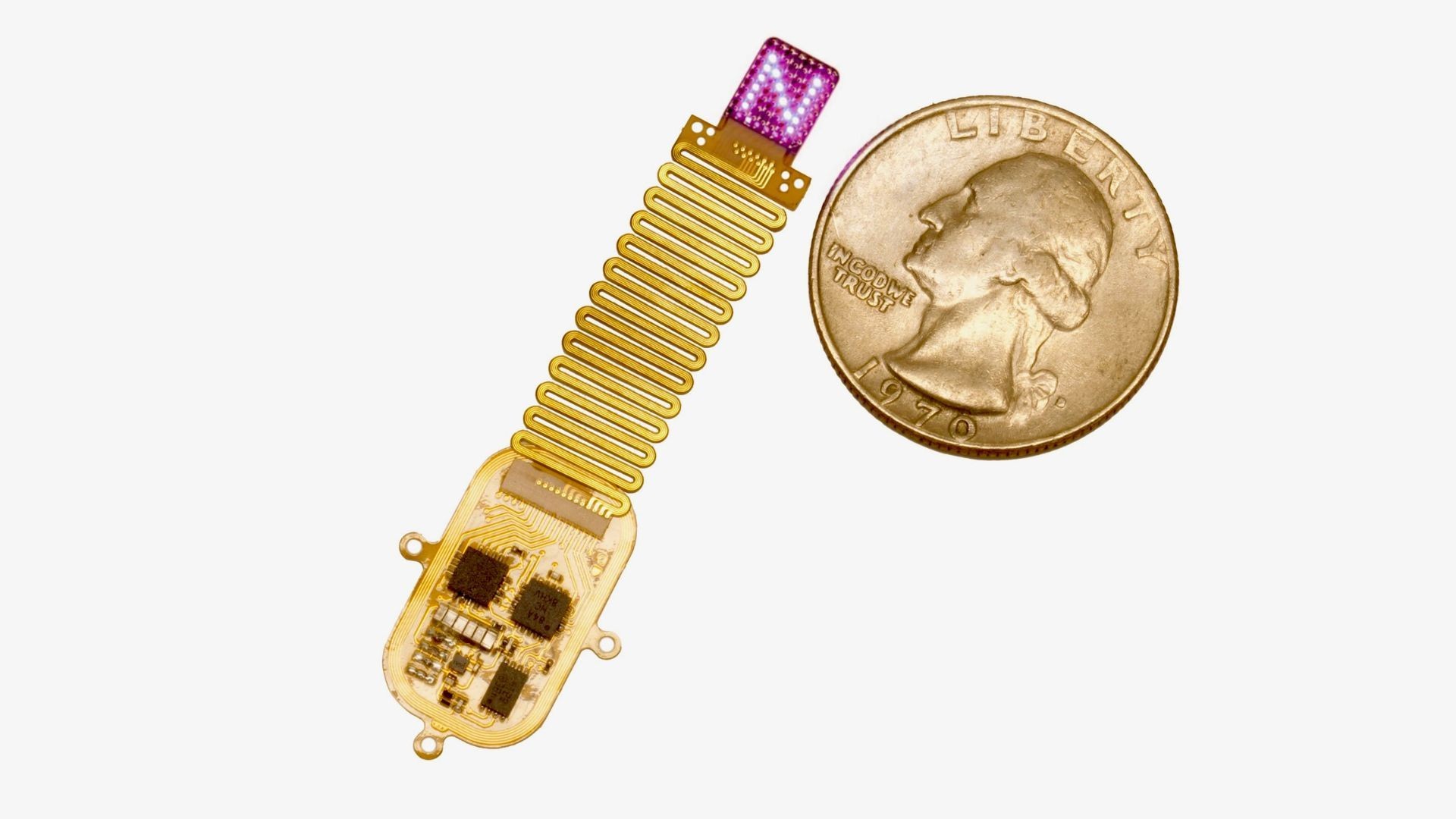

The device, smaller than a human finger, conforms to the skull’s curvature and contains 64 tiny LEDs, an electronic circuit, and a receiver antenna. It operates using near-field communication (NFC) — the same technology behind contactless card payments — to wirelessly control the LEDs. Unlike traditional BMIs requiring direct brain implants or bulky external hardware, this device sits under the scalp, projecting light directly onto the brain tissue.

The key is genetic modification. Brain cells don’t naturally respond to light, so researchers used gene editing to introduce light-sensitive ion channels into neurons. When activated by the LEDs, these channels trigger neural signals, allowing for precise control over brain activity. This technique, known as optogenetics, allows researchers to bypass the sensory system entirely.

Mouse Experiments Demonstrate Functionality

In experiments, mice were trained to associate specific light patterns with rewards. By wirelessly controlling the LEDs, researchers could instruct the device to produce different bursts of light, which the mice learned to recognize and respond to. For example, certain patterns guided them toward sugar water hidden in a lab maze.

“It’s like we can project a series of images — almost like play a movie — directly into the brain by controlling [the] sequence of patterns,” said John Rogers, the study’s senior author from Northwestern University.

The device isn’t limited to stimulating visual perception areas; it can activate neurons across the entire cortex, allowing for complex patterns of neural activity.

Implications for Future Research and Prosthetics

The team sees significant potential in prosthetics. This technology could add realistic sensations – like touch or pressure – to prosthetic limbs, or even restore auditory or visual input to patients with sensory impairments.

Bin He, a neuroengineering researcher at Carnegie Mellon University not involved in the study, called the technique “novel” and suggested it could have “various applications in neuroscience research using animal models… and beyond.”

However, regulatory hurdles remain. The biggest challenge is securing approval for the genetic modification component, as optogenetic techniques are just beginning to be explored in humans. While the device is expected to function similarly in humans, further testing is necessary.

This technology represents a powerful tool for fundamental neuroscience research. It allows scientists to bypass natural sensory channels and directly interface with the brain, opening new avenues for understanding neural processes. While human trials are still years away, this breakthrough marks a significant step toward a new generation of brain-machine interfaces.